It was sixty miles to the south entrance of Joshua Tree. My sister and I had discovered it by happy accident on a camping trip nearly thirty years earlier. Through the years it had always been a special place to visit. The Joshua Tree, a variety of yucca, look like a prophet with his arms raised. Throw in a number of giant expressive boulders and you have the makings for an otherworldly destination.

The plan was to drive through the park, and then take a run up to Pioneertown. At that point the trip would be over, all except the crying, and the explaining. In six weeks, I’d run up sixteen-thousand miles on the Mountain Bluebird. How would Avis respond to that? I could hardly wait to see.

Most of Joshua Tree was just more desert driving, looking through a bug-splattered window. It wasn’t until I got to Jumbo Rocks that things got a little interesting. This was the secret spot that my sister and I had discovered, perched on a rock with guitars beneath a full moon, listening to the wailing of the coyotes. One of the rocks, Skull Rock, does resemble an oblong skull. You can kind of see it. The traffic got bunched up here, people stopping for pictures. Jumbo Rocks has never been much of a secret. Now it was even less of one.

I’d had some interesting experiences at Joshua Tree. Once I spooked a herd of Big-horn sheep that rose up on high-heels and went clattering off. Then there was the bobcat crossing the road one early morning. Also, how could I forget my second seizure, one of three. Let’s not get into why it happened. Just trust me that it did. I went into town to get some firewood and was standing there looking at a psychedelic poster for an upcoming concert.

The next thing I knew, I woke up strapped flat to a board in the back of an ambulance. When I realized where I was and remembered I’d recently quit my job and didn’t have insurance, I begged them to let me go. They wouldn’t. As soon as they got me to the hospital, I jumped up and tried to escape. The doctor argued with me, but then let me go.

The hospital was far from town. I was just wearing a Led Zeppelin T-shirt and cut-off shorts. I stood out in the cold, dark night and spied on the hospital from a distance. A shuttle bus came up and I ran over and jumped on it. Unfortunately, it took me to Twenty-Nine Palms instead of back to Joshua Tree. I needed the last fifty dollars in my wallet to take a taxi back to my truck.

Since that time, I never felt exactly the same about Joshua Tree, especially after getting a five-thousand-dollar bill for the ambulance. Someone had made sure to go through my billfold and get my contact information while I was still unconscious.

Now I felt OK about things, not good, not bad. I drove past the Joshua Tree Saloon and the Inn where Gram Parsons died of an overdose. Not only had he made better music, he also had a better ambulance story, although not one he’d be telling anytime soon. I took the 62 to Sage Avenue, then took a left on Sunnyslope Drive.

Pioneertown is a movie set that was dreamed up in the 1940s by a team the included Roy Rogers, the Sons of the Pioneers, and Gene Autry. It was designed to be a place for both work and play and over the years over two hundred productions were filmed there. The on-site cantina later became the biker bar and live music venue, Pappy and Harriet’s, a true institute of California honky-tonk. Out back is the famous sign. Hippies Use the Side Door.

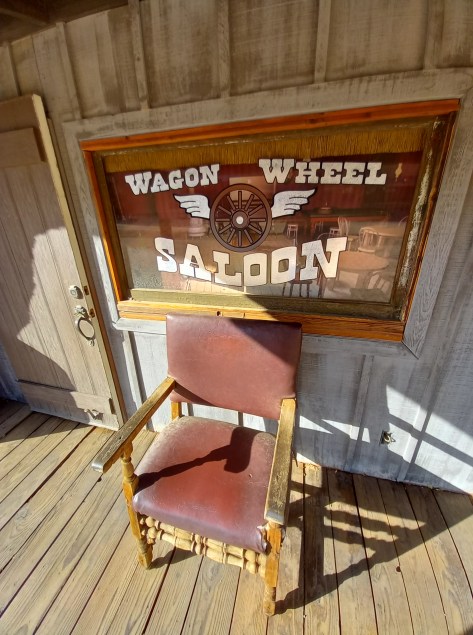

I parked the car and had the whole of Pioneertown to myself, if you didn’t include my shadow which staggered behind, some twenty feet long. There was the Film Museum, the Pioneertown Bank, the Wagon Wheel Saloon, now an actual wagon, and an actual l wheel. If I’d been a gunfighter my only opponent would’ve been my mind, which had already started future-tripping, now that the trip was almost up.

There were other things I should’ve spent the unemployment money on, like finding a job, a car, someplace permanent to live. What would happen next? Where would I go? Bang. Bang. Bang. I needed to shoot those thoughts dead. One thing at a time. It was still a hundred and twenty miles to Los Angeles. A lot could happen between now and then.

When I got back in the car, it was the first drive I hadn’t been looking forward to in the past six weeks. Up until now, all I’d wanted was to drive, drive, drive. Suddenly, I wasn’t in such a hurry. When I got to the giant turbine windmills that line the hills outside of Palm Desert, I wished that they could blow me back, back a week, two weeks, a month, with freedom still ahead of me, but the only choice I had was to go forward. The sun sat like a great white eye in the center of the road, and the clouds kept blowing past it like an endless succession of days.