There were two young guys in Hawaiian shirts at the desk when I checked into the hostel. I almost had to check the address again to make sure I was at the right place. It seemed too nice for a hostel. There was an adjoining restaurant and heated pool in the back. When I went up to the room, the bottom bunk I’d been assigned was one of those little cubicles with a curtain and a light and fan inside.

There was already someone in the room, a guy with a shaved head perched in the adjacent top bunk, looking like he wasn’t going anywhere for a while. We got to talking and I discovered that he was a refugee from the war in the Ukraine. His occupation in his country was a sommelier, or wine specialist, but he’d just come from working on a fish processor in Alaska and was hoping to get his foot in the door at any restaurant he could.

After relentlessly riding trains all over America for the past two weeks; from the West Coast to the Midwest, to the Northwest, back through the Great Plains, to the Northeast, down to the Deep South, it came as a great shock to be at the beach in Miami. It felt like I was in another country. I walked out of the hostel and crossed Collins Avenue, passing 5-star resorts to get to the ocean. The sky had gone back to being overcast, but rain didn’t appear eminent. Small greenish-gray waves washed up on the cultivated sand.

There was a walking trail that I started following south. The humidity was already causing my shorts to stick to my legs. Not many people were out yet. A few bicyclists passed by. Just following the lifeguard towers, which corresponded to the cross streets, in descending order, I eventually came to South Beach and made my way over to Ocean Drive. The atmosphere was festive. People were sitting on patios enjoying cocktails. The colors were tropical: pink, yellow, orange, aqua, green. The mannequins in the gift shops flashed the same neon themes on bikinis, tank tops, baseball and straw hats, and headbands. Outside of one bar a band of drag queens were getting warmed up for that night’s performance.

After passing the Art Deco Welcome Center in Lummus Park, I happened across two women dressed as Caribbean Carnival Queens, getting ready for a photo shoot. Some guy was harassing them and they shouted him down the street. I asked if I could take a picture, and after surmising the situation and concluding that I was harmless, just some passing old grandad, they nodded in assent. That was as close as I was to get to the glamor of the world-famous South Beach.

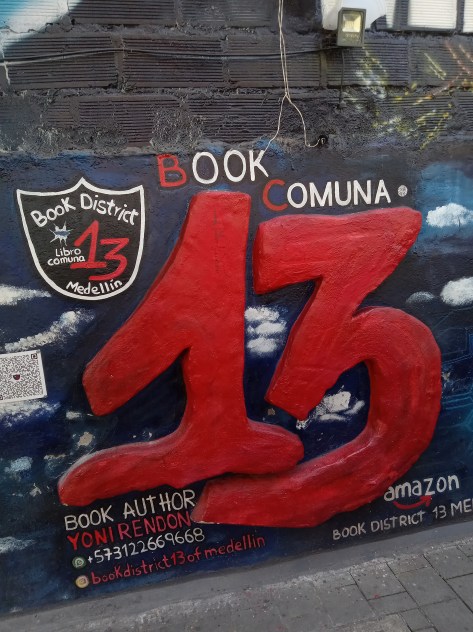

When I got back to the hostel, I realized that I better move fast if I was going to go anywhere anytime soon. I did a search on my phone and found a cheap roundtrip flight to Medellin leaving in two days, so just went ahead and booked it. It was doubtful I’d use the return, but would probably need evidence of onward travel once I got to the airport.

Someone had locked themselves in the bathroom up in my room, so I grabbed a swimsuit from my suitcase and went down to check out the pool. The colors changed every few minutes, from violet, to green, to blue. Dipping a toe into it, I discovered that the water was warmer than the air. One couple, in each other’s arms in the middle of pool, seemed like they were just getting to know each other. She was doing most of the talking, at one point trying to add up how many times she’d been to rehab.

Back in my room, I saw that the wine steward from the Ukraine had been joined by another roommate in the other top bunk, who peered down at me, like an emu, with a sharp face and black downy hair, and went back to what he was saying. They seemed to be having a great time together practicing their English and laughing out loud. Later, the guy from Ukraine asked me if I understood Portuguese, indicating that he didn’t understand one thing that the other guy was trying to say. I listened to him rattle on for a moment, and shook my head. I had no idea either. It wasn’t English, but didn’t seem to be Portuguese. It was like he was making up a new language as he went along.