I’ve spent a lifetime weathering storms / at the hem of each one / there has always been / a distant ripple of light / sometimes bright / and sometimes dim / like an ancient hymn / the thunder has lumbered across the plain / I’ve spent a lifetime weathering storms / but look / I still remain.

beautiful blue

riding the rails

riding the rails 1

It was the first day of fall and things were already falling apart. The first Uber driver I called totally ghosted me. That had never happened before. He was within a half mile of my pickup location when the driver rating and tip page suddenly flashed on my phone, as if his mission had been accomplished simply by driving past me. There was still time to call another driver, but if anxiety had already been gnawing at my stomach all morning, it was now devouring it. A trip of the magnitude of the one I was embarking on should’ve been thought out and researched for months. Instead, I was winging it, knowing full well that the price of failure could be disastrous. If you’re going to strand yourself anywhere with a shortage of cash, don’t let it be America.

My vague idea if nothing worked out was to take the Pacific Surfliner down to San Diego, and from there catch the Blue Line to San Ysidro, where I could cross the border into Tijuana, but I’d just come from Mexico and knew there was little escape to be found down there at the moment. What I wanted was to ride trains around the country. It was September. Everyone had wrapped up their vacations. The kids were back in school. The weather would still be decent everywhere, not too cold yet. The trees in the north would still have their leaves, only now beginning to change to yellow, red, and orange. I knew it could be done. I’d traveled on a USA Rail Pass three times in the past and had always gotten my money’s worth. The problem this time is that I hadn’t checked into anything, hadn’t made any inquiries or reservations, and was hoping I could just show up in Santa Ana and be on a train to Chicago within a few hours. Turns out it was going to be a little more complicated than that.

The second driver I contacted showed up in an electric car and quietly whisked me off to Santa Ana without any drama. He told me to reach out to Uber and let them know what had happened. They would take care of the nine-dollar charge that had just appeared on my account for a ride to Lake Park, a distance of about five blocks from where I was supposed to have been picked up. He may have been right, but as he pulled up in front of the Regional Transportation Center and I got out with my bags, which suddenly seemed ten times heavier than when I’d packed them that morning, I was sick with dread.

There was no one at the Amtrak window, but it was immediately evident that things were going haywire there as well. A message kept repeating over and over that the twelve o’clock train I’d been planning to take to Union Station in Los Angeles was running an hour late. They were blaming the delay on vandalism. Someone was out there getting back at the man by messing with the signals. Metrolink was being similarly impacted. There weren’t many passengers waiting, but the unfortunate ones who were there were sunken deep into the benches in dismay.

At one point I spotted some movement in the office, as if someone were hiding in the back room and only peeking to check if it was safe to come out. He had no choice but to come out now, but took his time doing so, with a pained expression on his face, as if I was an intruder tromping mud across the floor, as opposed to a customer looking to do business with the beleaguered railway line he was supposed to be working for.

Would I be able to catch the Southwest Chief to Chicago that evening? No, in fact, it was sold out. How about the Sunset Limited to New Orleans? That only ran three days a week. The Coast Starlight? Not until Saturday. What about a USA Rail Pass? Could I get one of those? It would probably be better to know where I was going first. What about Los Angeles? Could I head up there and figure things out at Union Station? That was possible, but the train was running late. Now an hour and a half late. Fine. I bought a one-way ticket to Los Angeles for seventeen dollars. That wasn’t going on the Rail Pass. The Rail Pass is good for ten sections. If it isn’t reserved for long-hauls, for example, from Los Angeles to Chicago, or New York City to Miami, it isn’t worth it.

Now I had a one-way ticket to Los Angeles, easily one of the most intimidating and expensive places in the country, with no idea what I’d do when I got there, especially since there seemed to be no availability on any of the outbound trains that day. The anxiety that had been eating up my stomach now extended into my skull and made it tingle in terror. I couldn’t sit still, so went out to pace beside the tracks. There was a high bridge to cross in order to get over to the tracks that run north, so I dragged my bags up the stairs and stood there staring down into the empty haze of the day.

There were a few passengers huddled beneath a shelter that I went over to join, setting my things on one side of it, and sitting down cross-legged in a narrow strip of shade. My idea had been that maybe I could calm myself a little by meditating, or at least counting my breaths, but within a minute I was joined by another man with a little plastic suitcase and lunch-pail, who sat down cross-legged beside me and began to read a book about relativity, while simultaneously speaking into a recorder, as if he were preparing for a debate on the merits of critical-thinking. At first, I thought he was questioning me.

Do you just believe what they want you to believe?

I looked over and saw him staring down into his recorder in victory, as if he’d just delivered a death blow to an unseen rival, which, fortunately, wasn’t me. At least not yet. Just then, a bell began to clang and I was delivered. The Pacific Surfliner was arriving from Irvine, way behind schedule. In only a few weeks, it wouldn’t be running at all, due to the unstable, shifting ground between Los Angeles and San Diego. Perhaps, I was just getting out by the skin of my teeth.

There were a lot of seats open on the train. I put my suitcase and backpack next to the luggage rack and took one that was facing backwards. Soon we were passing Angel Stadium in Anaheim and then making a brief stop at the Fullerton station. Things got industrial as we got closer to Los Angeles. Concrete riverbeds with streams of polluted green wastewater. Warehouses. Enormous freight yards and lots full of shipping containers. Graffiti splashed across the walls that faced the tracks like long, violent animated clips. Perched beneath some of the underpasses were homeless encampments, a mixture of tents and trash, the worst mutation of the camping experience the world has ever seen. We entered into a long tunnel before emerging at Union Station. I got out with my bags, as if my destination were death row, instead of a transportation hub, and made my way to the ticket office. If there wasn’t a train leaving the next day, my plan was to jump back on the Pacific Surfliner and head to Mexico. If there was a train the next day, I still had no idea what I’d do that night.

At the ticket window, I took a moment to gather all the diplomacy I could muster, before asking about the Southwest Chief, hoping to get a different answer than the one I’d gotten in Santa Ana. Actually, there was one seat left on the train I was told. Really? That was fantastic. When I asked about the Rail Pass, however, I was told it didn’t apply to the seat they had available. OK. What about the next day? Yes. There were some seats open the next day. I bought the pass and made the reservation. The train wasn’t leaving until six the following evening. Seeing that it was only two-thirty in the afternoon, that gave me a long time to kill.

Having lived in downtown Los Angeles for a few years, I knew what my options were, and they weren’t good. I knew all the crack hotels on Skid Row from back in the day, and even those aren’t cheap. One in particular, the Cecil, had recently been featured in a Netflix documentary when a tourist went missing and turned up floating in the water tank on the roof. I figured I’d go check it out, and just pay what I had to pay.

It had gotten to the point, where winding up in a water tank on the roof of the Cecil wasn’t the worst thing I could imagine. To be getting old in America, with no job or plan for the future, was way more frightening than that. Riding trains around the county wouldn’t solve anything, but it was all I could think to do. It felt like I was running for my life.

riding the rails 2

Leaving Union Station, I asked at the information desk about the paper schedules that used to line one of the walls, only to be told that they were only available online these days. I then asked the woman working there if she knew any hotels nearby, but the one she directed me to, the Metro Plaza Hotel, next to Oliveira Street, seemed like it would be too expensive, so I stopped just short of the door, and made my way back towards Oliveira Street.

Oliveira Street is home to the Angeles Pueblo, reported to be the first and oldest construction in the city, and is something of a miniature Mexican theme park, with traditional food and vendors selling some of the same wares you might find at the border. There was Norteno music being cranked up and when I got to the Plaza, saw that it was being supplied by a young DJ in a cowboy hat, and that a handful of couples were up dancing around the bandstand. It seemed like a leisurely way to spend a warm day. There were benches to rest on in the shade and a woman selling cold drinks. For me there was the anxiety of not knowing where I was going to sleep that night, however, so I passed quickly and headed for City Hall, figuring I’d make my way down to Central and the hotels on Skid Row. In addition to the Cecil, I also knew about the Roosevelt and a few others, really the most disgustingly bad deals on the face of the planet, but what could be done.

Getting there I had to cross the 101 freeway, and saw that the overpass was lined with tents. Seeing that made my stomach hurt, just like witnessing the encampments under the freeways. It is OK that people can be rich beyond their wildest dreams and live in mansions and fly their own private planes, but no one should have to live in that kind of squalor. The price of failure is too great in this country. Once you start falling you might never stop. There are countries where poor people still manage to maintain a quiet dignity. There are societies where families take care of their own. Here, homeless people end up totally isolated and go crazy, like Marvel Supervillains, as boisterous in their failure as the rich are in their revelry, being brought up to believe that they could’ve been anything, and now having it come to this and being told it’s all their fault. I’d been out of the country for years. Brought back by the pandemic and dislocated beyond measure, I was now waking up to that cold possibility every morning and the pain was very real.

From Central, I made my way down to Los Angeles Street and tracked down the King Eddy Saloon. Back in the day I’d sometimes be waiting for it to open at six in the morning. You could get a pitcher of Natural Lite for four twenty-five and a chicken potpie for a dollar. Half of Skid Row would be sitting there, getting a buzz on before the sun started rising. Since the time I’d left Los Angeles, however, there’d been a move to revitalize downtown, and now not only was the King Eddy boarded up, but all the hotels, even the Cecil, had been converted into expensive lofts. If the strategy is to price out the long-rooted transient, homeless population, they’ve still got a long way to go. I witnessed more tents and makeshift lean-tos on the street than you would expect at an intercontinental Boy Scout Jamboree.

Outside of the old Rosslyn Hotel I asked a security guard about places to stay in the area. He knew about a hotel a few blocks away that ended up being a boutique place for hipsters and urban professionals. The cheapest rooms started at two-hundred and fifty. Only when I was desperate beyond measure did it occur to me to do a search on my phone. What I discovered was that the Metro Plaza Hotel, back by the train station, was the best I could do on such short notice. Funny that I was almost on their doorstep earlier. It was a long trudge back.

The Metro Plaza Hotel is on the edge of Chinatown. The man working reception took a half hour to find my reservation. Seeing that I’d just made the booking on Expedia, I accepted that it might take a while, but then it started to feel like another bad sign, as if nothing about the trip had worked out so far, and this was just another example of bad planning and money I couldn’t afford to spend, flying out the window. When he finally did track down my reservation and handed me the key, the room I wound up in smelled like cigarette smoke, and from an adjoining door came the melodramatic strains of an Asian soap opera, interrupted every so often by a burst of lunatic chatter.

Now that I finally had a plan and place to stay for the night, I realized I hadn’t eaten all day, so grabbed whatever money was on the table and headed out the door, thinking I’d just grab something in Chinatown. On the way there I passed four young guys wearing Dodgers jerseys and asked if the Dodgers were playing that night. Of course, they were. I could see the lights of Dodger Stadium shining from where we stood. Now came a thought. The game didn’t start for an hour yet. Maybe I could walk up and check it out after I ate.

The restaurant I ducked into for noodles and orange chicken was unremarkable. Their unwillingness to give me a cup of water with my meal may have skewed my opinion. From there I walked through the Chinatown Central Plaza, past the statue of Bruce Lee, and over to Hop Louie, with its pagoda and paper lanterns. It was easy to see Dodger Stadium, hovering in the night sky like a pulsating UFO, but hard to know where to cross the 110 freeway to get to it. I finally googled directions and found a footbridge that crosses the freeway. As close as the stadium seemed, it turned into a long plod uphill, feeling like my shoes had been dipped in cement.

My idea had just been to walk up to the stadium, but once I got there, I realized I wouldn’t be happy if I didn’t make it inside the game. The Dodgers were on a streak, poised to have the winningest season in their history. Suddenly, I needed to get in. All I had was forty dollars. No credit card. No ID. Nothing else. Back in the day that would’ve been more than enough for a seat in the outfield, but now I didn’t know. Turns out that I could get in for thirty-five, but they no longer took money. You had to purchase the ticket on a ballpark app. The woman who explained this to me was firm. No ballpark app, no game. No game? No game.

I stepped back and tried to think. At that point my phone seemed to lose its connection to the internet. The app I tried to download went spinning into infinity and even while it was doing so, I knew full well I didn’t have my credit card information to purchase a ticket. This couldn’t be happening. There was a kid working the gate that I went over and flashed my money at. He’d get it. He’d know. What is this world coming to when they don’t take money anymore?

The kid just shrugged at my dilemma and when I asked if there was an area where guys might be scalping tickets, he looked worried and glanced over at security. There was no one that I could see, with their hat pulled low, flashing tickets, and it began to dawn on me that I probably wasn’t going to get into the game. That just fit the pattern of the day perfectly. Trains not running. Hotels not operating. Baseball games that don’t take money. This was clearly the last trip of my life and it was all going downhill so far.

In the box office there was another woman working, an older one who hadn’t heard my sob story yet. Before giving up, I approached her and explained the situation. She sympathized and went to work on finding a solution, eventually buying me a ticket on her own credit card and having me pay her back with the cash. It was the last thing I expected to find, a real human with a real heart, going against the grain, doing whatever it took to get a fan into the game. Beyond thanking her, I should’ve led her out on the field during the seventh inning stretch and let the crowd know about the secret hero they had in their midst. I’d stumbled across that rarest of finds. Someone who actually cares.

Five minutes later I was sitting above left field in a sea of empty seats. Strange to be way up there looking down on the lights of downtown after the way the day had started and mostly stayed. It made me think that perhaps there might be a chance after all. If one person could care, maybe there were other people who cared out there as well. Maybe there was a solution, a hope, a future beyond the grim one that perpetually tortured me to the point where I was jumping out of my skin.

It wasn’t much of a game against the Diamondbacks. For most of it the score was tied at one a piece. Then in the ninth the D-backs got a solo homerun shot. It might’ve been safe to assume that the game was over. Suddenly the bases were loaded, however, and the score was tied. At that point, Mookie Betts, who’d been sitting out most of the game, came into pinch-hit and hit a single, driving in the winning run. The crowd leapt to their feet and now, strangely, inexplicably, instead of jumping out of my skin in angst, I was jumping around in joy.

Perhaps that was the moment that my trip really got underway. It was going to have its good and bad moments, and there was no way of telling when or what order they’d come in. That is the beauty about heading off into the unknown. I didn’t know what was going to happen next, and that was way better than thinking that I did and waking up every morning barely able to face the day.

riding the rails 3

Check out was at twelve o’clock and since I was paying so much for the room and still had so much time to kill before the Southwest Chief departed that evening, I wasn’t prepared to give it up until twelve o’clock on the dot. That gave me time to download and study some of the train schedules. I already knew and had ridden most of the long-haul routes, the Southwest Chief, the Sunset Limited, the Texas Eagle, the Coast Starlight, the City of New Orleans, the Lakeshore Limited, the Crescent, the Silver Star. What was important to know was what days they ran and what times they departed and arrived. The best thing possible is to be able to just hop from one train to the next. Most of the time it requires an overnight stay, however, so I’d have to download an app for hostels as well. One thing I could not afford was to be stranded in a big city, paying a lot for accommodation.

When I was in college I’d gotten to study in England and do some traveling in Europe, so had been introduced to the hostel system, shared rooms, often with bunkbeds, and shared bathrooms and cooking facilities. I’d never heard about anyone staying in a hostel growing up. No one I knew had ever done much traveling. The assumption seemed to be that you would need a lot of money and possibly some connections if you wished to do so. In Europe I met kids, however, often without much money, who were traveling all over the world in ways I never dreamed possible.

My preference is to go to affordable countries, where a single room can be found at a reasonable price. Latin America and Southeast Asia have been such destinations in the past, although prices seem to be going up all over the globe. If it comes to needing a cheap place to crash, I still do hostels, when necessary, particularly in Europe or some of the big cities in America where they’ve begun to spring up. It doesn’t pay to go bankrupt if all you really need to do is lie down for a few hours.

The Hotel Metro Plaza let me store my things behind the desk once I’d checked out, which was convenient seeing that Union Station was right across the street. My plan was to go back and revisit some of the old haunts from my days of living downtown. Ah, the good old days when I’d lost my mind and completely fallen out of society.

From Spring Street, I walked past City Hall and the Criminal Courts building, then took First up to Broadway. What is left of the historical core of downtown Los Angeles is buried as deep in years of neglect as ancient Pompei is in volcanic ashes, but if you know where to look you can see signs of it. I walked past the Central Market and Clifton’s Cafeteria, where my grandfather used to eat as a young man, before the city, in coordination with the automobile industry, replaced all of the streetcar lines with freeways, creating the first car city in America and dooming future residents to a gridlocked dystopia, with over 500 reported incidents of road rage in one year alone.

As the name might suggest, Broadway is also home to a number of historic theaters, some of which have been refurbished and are back to hosting concerts and events. The Los Angeles Theater had something going on called Metal and Monsters. The Globe was advertising travesuras, which translated to antics, or mischievous conduct, when I looked it up. Joe Satriani was playing at the Orpheum, and a few blocks over, at the Mayan, there were two acts on the marquee, Minimal Effect and Detroit Love.

The place I was really interested in tracking down was the Stillwell Hotel, on the corner of 8th and Grand, where’d I’d lived my last two years in Los Angeles, dreaming dreams so big all they did was send me over the edge. I’d paid five-fifty a month the first year, and six-fifty the second, for a room that included room service once a week, with an Indian restaurant on the ground floor, as well as the famous Hank’s Bar, which I would descend to nightly in the elevator, like Batman sliding down the pole to the Batcave. The Hotel was still there. Hank’s was still there. The Indian restaurant was still there, but looked like they were only open for take-out. I asked the guy at the desk if they still rented rooms on a monthly basis, but the answer was negative. Apparently, during COVID they’d tried to fill the hotel with homeless folks and the owner had put his foot down and stopped taking new residents altogether. That was a pity. There was nowhere even remotely affordable left in the city, as far as I could tell.

From the Stillwell I walked up and through the Central Library, where I’d spent long hours checking out books and world music CDs that I would take back to my room and burn, never listening to one of them, just burning boxes of CDs that never got played, kind of like the CDs of my own music I was producing at the time. The library was one place still enforcing the mask mandate, so I dug one out of my pocket and put it on, just to walk to the door on the other side, pass through, and climb the steps to Bunker Hill. There was my old YMCA, the best in the world. It occurred to me then, quite sadly, that no matter how bad things had seemed back then, they were way worse now.

The Arts District was a long way from Bunker Hill, but it was a walk I was intent on making. I had four hours before the train left and there were things I still wanted to see. On the way I passed Pershing Square with its strange, purple tower, crossed Broadway again, and then headed down 5th, back in the direction of Skid Row and the King Eddy Saloon. As far back as the 1930s, there’d already been upwards of ten thousand homeless folks crammed into the one square mile of Skid Row. For most of its existence the policy was one of containment, like locking a bunch of wild animals in the same cage. They might hurt each other but can’t get at anyone else. I crossed Los Angeles Street and walked past the Los Angeles Mission, which seemed oddly vacant on this day. Perhaps everyone was being housed in the big tents that lined Sixth Street all the way to Alameda.

At the Little Tokyo Market Place, I had to stop and get an iced tea. Twenty-five earlier, after making my first record and moving downtown, I’d gotten hired to do patch work on the roof. The guy who’d engineered the record got me the gig and I’d spent a few miserable weeks up to my elbows in black tar, before the rains of El Nino put us on a permanent hiatus. It wasn’t much money, but more than I’d ever get playing gigs and selling CDs. No. That was never going to happen.

Walking up Hewitt was like walking through a dream, as I got closer to the American Hotel on the corner of Traction. That had been a lucky find and good, if brief, time of life. If we hadn’t recorded my record right across the street from it, I never would’ve known about it or the famous Al’s Bar downstairs. As luck would have it, I was able to get a room there shortly thereafter, four hundred dollars a month, if I remember right, and there began my life in Los Angeles. There would be three or four bands playing every night and the floorboards would be shaking too hard to fall asleep, but who wanted to sleep? If all I’d wanted was to party and play foosball, I’d come to the right place.

Al’s Bar closed down in 2001, but the American Hotel is still in business, either that or back in business. Four nights probably costs the same as a month used to, and you probably won’t be sleeping on a hairy futon in a closet-sized room, adorned with snot and punk rock stickers. That kind of charm can’t, and maybe shouldn’t be, recaptured.

By now, I realized I should probably head back up to Chinatown and get my bags. I needed some time at the station to prepare for my upcoming ordeal. Passing Oliveira Street, I heard the same Norteno music from the day before and saw some of the same couples dancing in the plaza. I’m getting old and should’ve been sitting on a bench in the shade, drinking a Jamaica and reminiscing with acquaintances about the way things used to be, not jumping on a train with no idea what I was doing or where I was going.

Was this another adventure I was chasing or just more madness? There seemed to be no difference anymore. If there’d ever been an easy option, it no longer existed. I’d pushed things too hard and too far to ever get back what I’d given up or passed on, and though by now the cost had become unbearably steep, the only way to keep desperation at bay was to just keep moving. So, that’s what I intended to do.

riding the rails 4

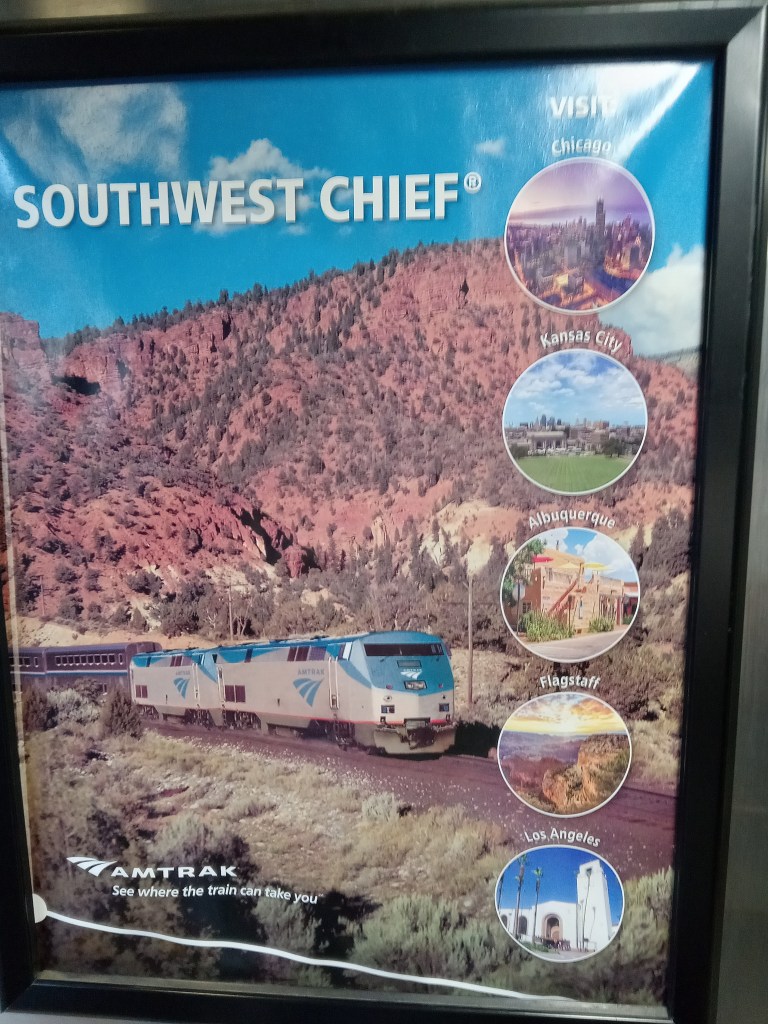

The Southwest Chief is roughly 2,300 miles long and runs from Los Angeles to Chicago, passing through Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Kansas, Iowa, and Illinois. Before all the independent lines were consolidated in 1971 under the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, which became known as Amtrak, it was called the Super Chief and was operated by the Santa Fe Railway.

After grabbing my bags at the Hotel Metro Plaza, I headed over to Union Station, which looks like an old Spanish Mission on the outside and an opera hall on the inside. Riding the train can be like traveling back in time. I’d always envied the explorers and pioneers, who’d made the journey out west, back when America was a land of unlimited opportunity. By the time I got out of school, there was no place you could just show up and not be trespassing. It could even be considered a crime to sleep in your car, if you could afford one. As long as my Rail Pass was good, I had a place to be. After that I’d need to find something fast, which probably meant leaving the country.

I checked in and requested a window seat. The gate had yet to be announced, so I went over to sit down in the cavernous waiting room. The chairs were roped off. You needed to prove you had a ticket to enter and sit down, so I was curious about a guy who appeared to be homeless, his bags scattered all over the floor, laughing at jokes that no one could hear and speaking a stream of unintelligible gibberish. It was hard to contain my dismay then, when we finally boarded the train, and he ended up on my coach, only a few seats back. He couldn’t sit still and began to pace the aisles, his pants down to his knees, flapping his hands in the air. The tag above his seat indicated that he was going all the way to Chicago. It was an inauspicious way to begin the trip.

When we pulled out of Union Station, the train retraced the tracks I’d arrived on the day before, past the same riverbeds, graffiti and industrial rooftops, stopping once again at the Fullerton Station. Then we headed east, reaching Riverside by dusk and San Bernadino by nightfall. A short while later it was Victorville. The car I was in was still pretty empty. Everyone had two seats to themselves. Young homey would be up pacing the aisles for the duration of the trip. It was clear he was high on something, but on what, I wasn’t sure. He appeared to be harmless, almost autistic, but was definitely a nuisance.

The first stop we came to where we were allowed to get off the train for a smoke break and to stretch our legs was Barstow. It was cold out and I wandered the platform, feeling like I should join a conversation circle, but lacking the appropriate vice to do so. I took pictures of the sides of the train and the Amtrak logo, then walked behind it and took pictures of the caboose, the two red lights flashing like the eyes of a silver robot.

After leaving Barstow, the overhead lights turned blue, with a matching set of green lights running down a strip on the floor. The desert outside was dark and the train rocked back and forth, the whistle blowing incessantly, giving voice to the sorrow and angst that was rising in my soul. In the blue light I caught my reflection, the same reflection I’d been seeing in bus, train, airplane, and boat windows for years now, once as a young man with a dream in his eye, now as a battered, blown-out old one, still desperately clutching to that dream because there was nothing left to hold onto. Had it ever come true? In some ways, it had. Had it mostly been a nightmare? There was no question that it had.