Sometime during the middle of the night, not long after passing through Needles, the train stopped dead on the tracks and just sat there for a long time. I knew they had to yield the tracks to freight trains from time to time, and hoped that it was that and not a mechanical issue. Behind me a Mexican with a baseball hat was leaning back in his seat with his mouth wide open, snoring as if he’d swallowed a rattlesnake and was trying to choke it back up. Behind him the guy who’d been on the phone all night, talking to women from foreign countries, promising to send them money, took the opportunity to call another one.

Habibi, I heard him greet her. You know I’m not wealthy. Rich. I’m not rich. But I will send you something. I also heard him complain about the guy, right behind him, who couldn’t keep his mouth shut and had been pacing the aisles all night. It’s the drugs, I heard him explain to her. In America we’ve got a lot of people hooked on drugs.

Once we got underway again, I bent over and tried to sleep. I’d pulled out the leg rests on both of the seats and could just cram into a horizontal position with my knees drawn up against my chest and a thin sweatshirt between my head and the headrest. The train managed to rock me to sleep, over and over again, but I kept waking up in fear. Why had I lived this long? I’d missed my chance to go out with any dignity fifteen years earlier, when I’d still been in Los Angeles, wrapping up my final record. Since then, I’d wandered the world like a hungry ghost, inventing new ways to suffer.

The guy two seats back got on the phone with another woman. How’s my little monkey, I heard him ask.

I passed out and woke up to a pink and purple sky. The sun was beginning to rise over the desert. A yellow crown appeared and was reflected in a narrow stretch of water that had gathered beside the tracks. In the distance, beyond the scrub brush, were a series of flat-top mountains. By now we’d already passed Flagstaff.

Around eight, I went to get a cup of coffee at the café and sat drinking it in the observation car as we pulled into Gallup, New Mexico. I’d been through Gallup the year before and recognized some of the Zuni trading posts. Waiting to board the train was a young guy in a blue suit jacket and black sunglasses, looking like he was on his way to audition for a Blues Brothers cover band. The train was heading to Chicago, after all. When I went to my seat to grab my charger, I saw he’d been given the seat next to mine.

Back in the observation car, I noticed another musical type, now sitting at the far end with a guitar on his lap. As we pulled out of the station, he began to serenade us with fingerpicking music that was the perfect soundtrack for a journey across the high plain. When he took a break, I complimented him and found out that he was a songwriter from Pasadena on his way to try his luck in New York. We talked about the music scene in Los Angeles and how difficult it is to gather any momentum. It used to be that there were very few entertainment options available and a huge audience for them. Nowadays, with the internet, social media, and streaming, there is endless content and if an audience exists at all, it is one with a diminished attention span. Mark, as he introduced himself, was hoping to make a record anyway.

Just then there was a call for emergency services from the dining car. They were looking for a doctor or nurse, anyone with a medical background. A few minutes later, young homey emerged, trailed by a concerned crew member. Apparently, he could speak coherently when required to, and was insisting that he was all right. My hope was that they’d kick him off the train before long. We still had over thirty hours before we got to Chicago.

At a nearby table there was another guy who might require an intervention at some point, already starting in on his third whiskey coke of the morning. He’d intruded on a couple, the guy in a paisley sweatshirt, the woman tattooed and looking recently beat up. He was angry about the no smoking policy. What he really wanted to do was get high and wondered if he could smoke his vape in the bathroom.

It was time to try to book my next leg of the trip. I’d studied all the schedules and what seemed to make sense was to head to Miami straight away, as it was the one place I really wanted to see. Years earlier, I’d traveled from Miami to Washington DC on the Silver Star, but didn’t recall much, since my condition at the time had been close to that of the guy looking to get high in the bathroom. Florida seemed like the most exotic place I could get to on the train, something different. All the other places, I’d been to many times before.

With a Rail Pass, all you need to reserve the next section of your trip is call 1 800 USA RAIL. As soon as I was able to interject myself into the menu, I asked to speak to a representative. After ten minutes on hold, I got to talk to a real, live person. She was able to get me on the Capitol Limited the day after my arrival, with a direct connection to Miami from DC. I’d have to spend one night in Chicago. The next step then, was to find a hostel. Looking on Hostelworld, I found one a mile from the station that would work. It was forty dollars for a shared room with six bunks in it.

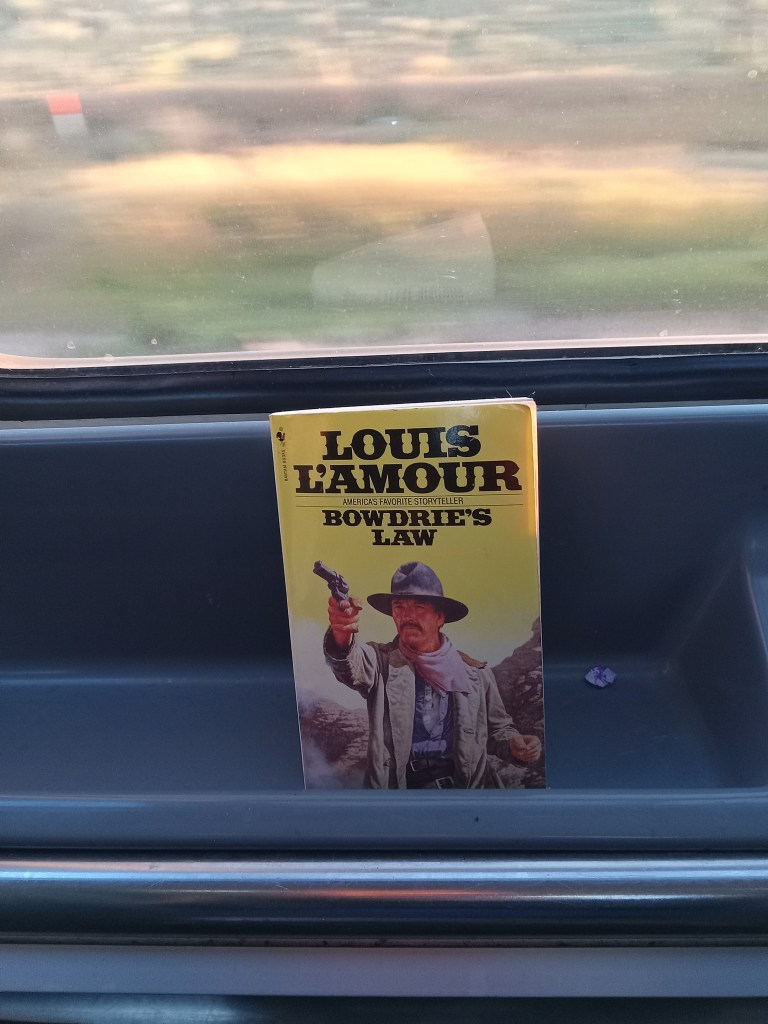

Now that I had the next few days straightened out, it felt like a could relax a little and enjoy the view. The range outside the window looked like one a cowboy would go galloping across in a Western. There were herds of cattle grazing on the bleached grass. Mark sat at the end of the observation car playing a plaintive ballad that sounded like something Sergio Leone would’ve come up with. When I asked him about it, he admitted it was a song by Madonna he’d been trying to learn. I never would’ve guessed.