The Coast Starlight wasn’t leaving until 9:50, so that gave me time to take a shower and eat breakfast. It wouldn’t take long to get to the station, but I didn’t want to get there too late and get stuck with an aisle seat. The whole point of taking the trip was to see the country, and I didn’t want to have to look over someone’s head to do so.

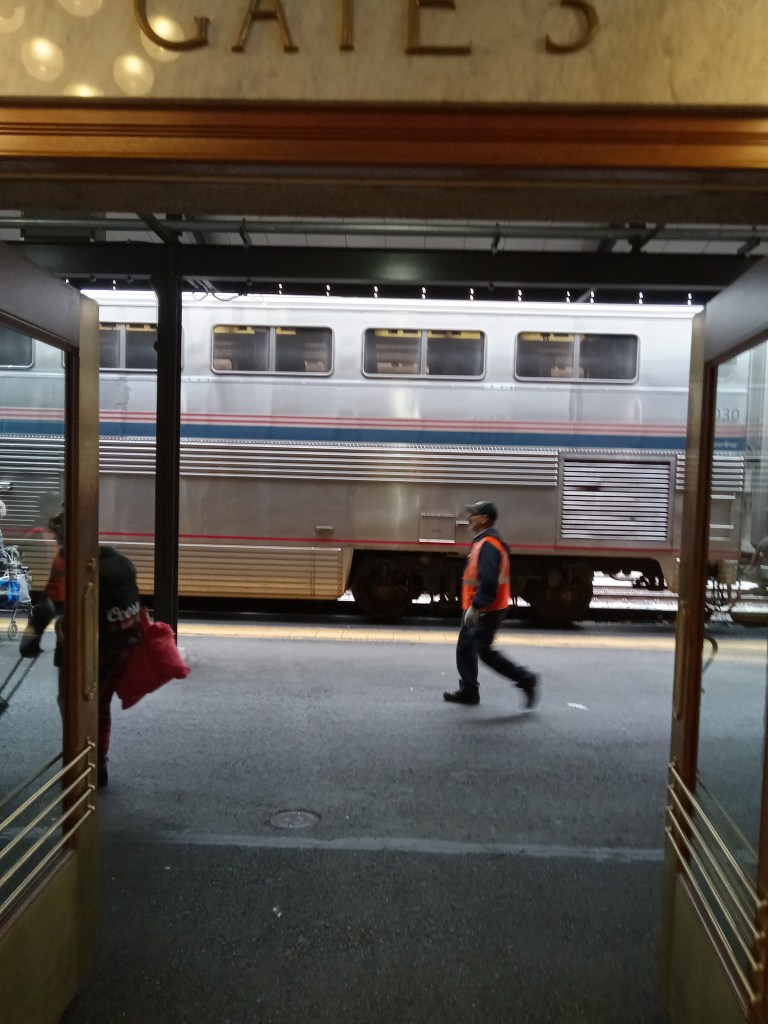

By the time I got to King Street Station, people were already standing in line to board the train. I ended up in seat 33, which was the window seat I wanted. Behind me was a German couple, who’d already unpacked their bedding and reclined their seats all the way back. An old hippie that I’d seen checking out of the hostel that morning came up the stairs and headed for the rear of the train.

The Coast Starlight has been in operation since Amtrak consolidated most of the independent railway lines in 1971, and is named for two trains that had previously been run by the Southern Pacific, the Coast Daylight and the Starlight. It covers almost the entire length of the West Coast, from Los Angeles to Seattle, and many points in between. I’d probably taken the train three or four times and like it because it passes through a lot of my old stomping grounds. On this particular train I could tell I was back with the West Coast freak crowd. One bemused old-timer who was having a hard time finding his seat let all of us know that riding the train wasn’t just a job, it was an adventure.

With my primitive grasp of technology and innovations like cloud storage for safeguarding data, I have been relying on an external drive for years. I will take pictures on my phone, then transfer them to my laptop and back them up on the drive. This has some serious drawbacks, such as someone potentially robbing me and getting away with my phone, laptop, and drive all at once, but so far, I’ve avoided that happening. There was an episode on a night bus in Jakarta once where a thief got away with my camera and laptop, but I had the external drive strapped to my body, in the same way that a spy packs a pistol. Thank God for that. I’d just spent a month in India, one in Sri Lanka, and a third in Indonesia, and all that documentation would’ve been lost forever if I hadn’t been so paranoid.

Now I was about to do something stupid that never would have been an issue if I’d switched over to the cloud by now. The memory on my phone was nearly full and I wanted to start off on the Coast Starlight with a blank slate. I got out my laptop and started downloading the pictures on my phone, but it was taking longer than usual and the train pulled out of the station. There were images I didn’t want to miss, so I picked up my camera and took a few pictures while the transfer process was still going on. When it finally finished, there were twice as many pictures in the folder and some were out of order and not the right size anymore. I became so stressed trying to remedy the situation that the next time I looked up we were just outside Tacoma. Eventually, I found that the pictures were there. The miniatures were just replicas that had been shuffled into the sequence out of order. It would take a long time to go through them all, but at least I hadn’t destroyed all the pictures I’d taken between Kansas City and Seattle, which would’ve been devastating.

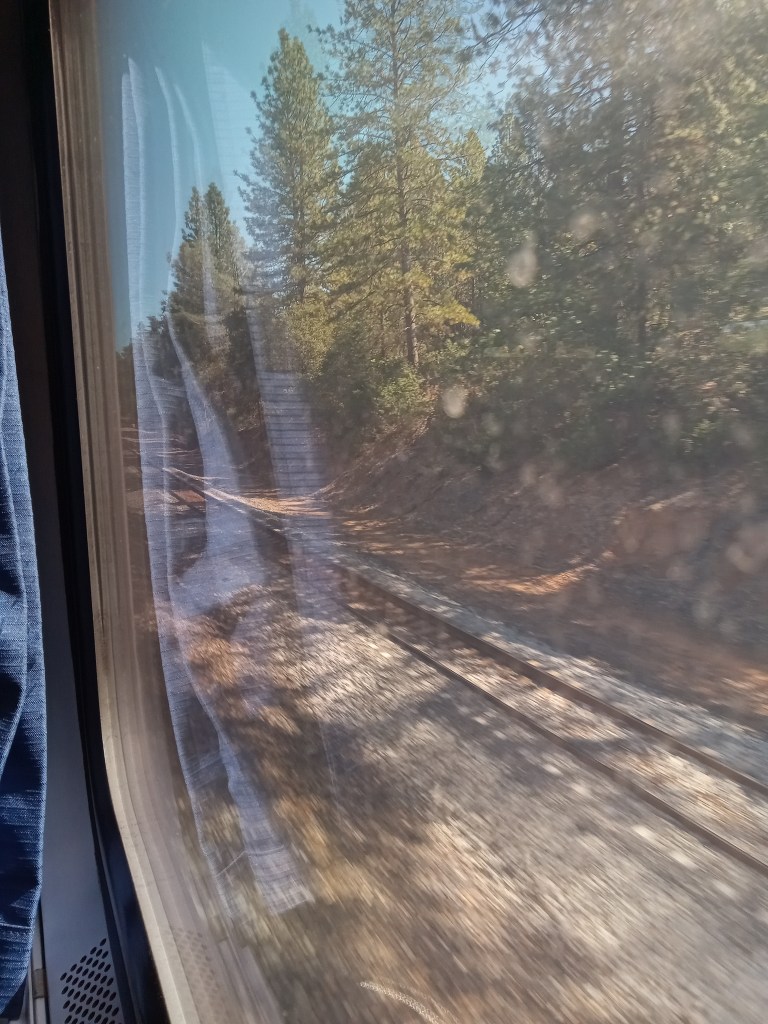

It was overcast outside and cold on the train. The attendant was having problems keeping people in their assigned seats. There were too many anarchists aboard. There were brief stops in Olympia and Centralia. Then we came to Kelso. The dining car was running late. The twelve-thirty seating time had been moved back fifteen minutes. Only those who were traveling in the sleepers were allowed to eat in the dining car. At twenty-five dollars for lunch and forty-five dollars for dinner, they were the only ones who could afford it anyway. By now I’d eaten four or five of the microwaveable cheeseburgers, which came out like bags of hot glue, but were strangely tasty once you got used to them. Before they closed for the night, I always made sure to grab a bag of pretzels and a bottle of water. The water onboard was allegedly potable, but had come out cloudy and tasted like coolant the one time I filled an empty bottle to save money.

At Vancouver we crossed over the Columbia River and soon arrived in Portland, where we had a thirty-minute layover. There wasn’t time to wander far, so I just walked through the station and stepped out in front for a few minutes. The Union Station in Portland is memorable because of the big clock tower that says GO BY TRAIN. People didn’t always need this prompt. Between 1900 and 1940, the Golden Age of railroads, most travel was done by train, but following the Second World War, the competition from airlines and the auto industry caused ridership to plummet. These days almost no one takes the train, unless it’s to work. When they do talk about taking a trip on the train, it is generally regard as a novelty, something they wouldn’t ordinarily consider, but hey, why not? That could be fun.

There were a lot of passengers getting on at Portland and when I reboarded there was a teenaged girl in the seat next to mine, wearing Doc Marten boots and writing in a journal. I headed straight to the observation car. Eugene was coming up and I wanted to see what it looked like, even though I’d been there a few years earlier, as well. I’d lived a short time there after college and still have a lot of affection for the place, even though it didn’t work out all that well for me in the end. We passed Salem and Albany, but I wasn’t paying much attention. It was Eugene I was interested in. As we reached the outskirts and I began to recognize some of the landmarks, I became dizzy with nostalgia. There was Willamette Park. There was Skinner’s Butte. I could almost see myself up there as a twenty-three-year-old, with a guitar strung around my neck, watching the train come in. I wondered how everyone was doing up at the old High Street Brewery? Would there be a blues band playing tonight at Taylor’s?

We had about ten minutes to get out and stretch. The crowd milling around the platform was the same counterculture stalwarts I associated with Eugene. There was the Jesus guy with his round sunglasses and sandals. There was the yoga girl, with her mat under one arm and a guitar under the other. There was the fake gangster. He was actually from Chico. A couple guys in backwards baseball hats were kneeling down by the Eugene sign packing bowls.

Right when we were ready to depart, a young woman appeared on the tracks, shouting for us to wait, she was coming. It wasn’t possible for her to run, but she still tired herself out to the point that she fell to her knees just outside the door and it took half of the crew to get her onboard. For the next twenty minutes she squatted on the floor, hyperventilating and trying to explain about her asthma. Finally, she was OK, and very apologetic to everybody. She wanted everyone to know it was her asthma that made her almost miss the train.

I’d been monitoring the situation in Florida every chance I could get, but only now received confirmation that I’d made the right decision, when I saw that Amtrack had suspended their Silver Star service to Miami, at least until the end of the week. Hurricane Ian had made landfall in Fort Myers the day before. The damage was said to be catastrophic. Now it was making its way towards the Carolinas. No one could say when, if ever, things would be getting back to normal.

The girl in the Doc Martens had left the train and another one had taken her place. I saw her suitcase on the floor, but not her. She was up in the observation car reading a book, but I wouldn’t make that connection until later. I was up there myself when a Goodwill cowboy came in. He’d gotten on the train in Klamath Falls, and had the hat, boots, corduroy coat, and all, but they were mismatched. The brim on the hat was too small, with a strap under the chin, like something an Australian would wear to a rodeo. I thought about the hero in the Louis L’Amour story I’d just read. He wouldn’t be caught dead in something like that. All of his outfits had to be color-coded, right down to the bandana he chose. The guy was looking to rustle up some grub, but the café car was closed for another half hour. When he found that out, he sighed and sauntered back down the aisle.

Returning to my seat, I found the girl next to me had finally set up camp. She’d decided to keep her suitcase on the ground in front of her, so getting around her during the night was going to be a challenge. In a sense I’d been lucky. Out of five nights riding the train, this is the first time I’d needed to share the seat with someone else. It would be interesting to see how that was going to affect my tailbone, which now seemed to be hurting all the time.

Sometime during the night, I passed out and collapsed into the crack between the seat and window. When I woke up it was pitch black and my neck and right arm were almost paralyzed. I sat munching on a bag of pretzels, one by one, and waited for the sun to rise. We were still two hours outside of Sacramento.